I asked Dylan once, Did you make Gene Clark famous? And he said, No, Gene Clark made me famous.

-Bobby Neuwirth

On the night of January 16, 1991, Gene Clark and the four other original Byrds got together one last time to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The Eagle Don Henley makes the introduction. Only McGuinn has a guitar, just like the original version of the song. Crosby up front, the endearingly portly, proud, slightly daft cosmic sailor, sideman extraordinaire handsome Chris Hillman; and stage left, looking awkward without their instruments, wan with illness, drummer Michael Clarke, and next to him the Tambourine Man himself, Gene Clark.

The ceremony was held at the Waldorf Astoria in New York. I was there, covering the moment ostensibly for Rolling Stone although the chances of anything I wrote seeing the light of day were pretty slim and none then.

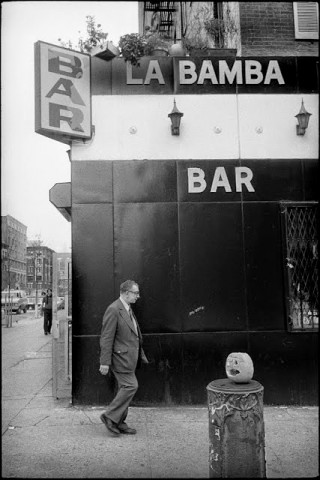

photograph by Ted Barron

Crosby was clean after a year’s stint in Federal Prison in Huntsville Texas. The Clark(e) boys were not quite; both would be dead within the year. That night also marked the beginning of America’s war with Iraq and my brother’s special forces unit was the tip of the spear. Without me, his twin. Gene was glad to see me. And I him, though we were both a little ashamed to look too close. Especially when we bumped into each other coming out of opposite bathroom stalls.

You all right, little brother? he asked in his John Wayne prairie accent, his sheepish nature covered by Rock Star brio.

Wait for me, he said. Let’s talk after the show. The boys played Mr. Tambourine Man, Turn Turn Turn and Feel A Whole Lot Better with my man Gene on lead vocals. In all it was a beautiful and buoyant night; I was happy for him.

Because Gene Clark and I go back to the days when my mother worked in a bar and my dad out of a bakery truck. On the fateful morning in question, I went to see mom first.

At the Village Idiot, on 1st Ave around 9th St, a place known for skeeviness, a honky tonk jukebox and lovely barmaids.

The story went that my mother started working there when she got pregnant with me and Diz. That’s my little brother, by five minutes. He used to hit his head a lot, a polite way why he got his nickname. It’s nicer than calling him retard like the bullies at our school. We got into a lot of fights until he told me, Stop that.

I remember because he seldom said anything; everyone called him that but he was just quiet and a little angry. I think personally he was trying to compose himself. He was born breach; my lungs worked but his did not. He got stuck in my mother coming out. And then when we were barely learning to stand tumble and fall, his hands got burned on the slide.

My dad was there and he grabbed and ran with him the twenty five blocks from the playground at Tompkins to Bellview in his arms with me a stoplight behind waiting at the crossings like a good boy while dad went wailing out into the intersections past beeping trucks and swerving cars with his hysterically screaming baby in his arms. It was the day that I certainly learned to walk. When he told that story over a Kool after booting up, it was that he could see the skin peeling up from Diz’s palms.

My father used to tell me this story and all the others that made up our family history when he was high. It’s a junkie story so each day is a different piece of it.

Where were we? he’d say. But that’s for later.

First I went to see my mom. It was okay in the bar in the early afternoon and when I went to school to pretend I was doing homework, and play some songs on the jukebox. This was the very beginning of the whole punk thing and we had some Dolls singles. The rest of it was country, including an oddball 45 RPM record by something called The Dillard and Clark Expedition.

There were just a few regulars in the bar in the early afternoon. It did not start to get busy until around five. We played hooky until then and I would go and write with my schoolboy composition notebook.

I think maybe mom knew we had skipped out of school but in her mind we could go back. She talked about it that way, hinting at the truth. I hated to disappoint her; Diz was beyond caring.

This is the way our family lived; we seldom talked about what we were supposed to be talking about and my mom wasn’t completely drunk yet and if my dad got high in time he might come in and Diz and it’s like we were the family we never were with the afternoon Western NY sun going down over the Hudson through the big plate glass window in front. We knew the guy who painted the window. That’s the way it was in the city then; everyone talks about how wild it was and it was, but it was also like a small town and you knew everyone and everyone took care of each other. Everyone we knew were junkies or bar people and the one thing the AA’s got right in that book was how drunks take care of each other.

Down Hard to the End. It was the circus life for us.

Originally posted at the East of Bowery Blog. Words by Drew Hubner, photographs by Ted Barron.

Stories